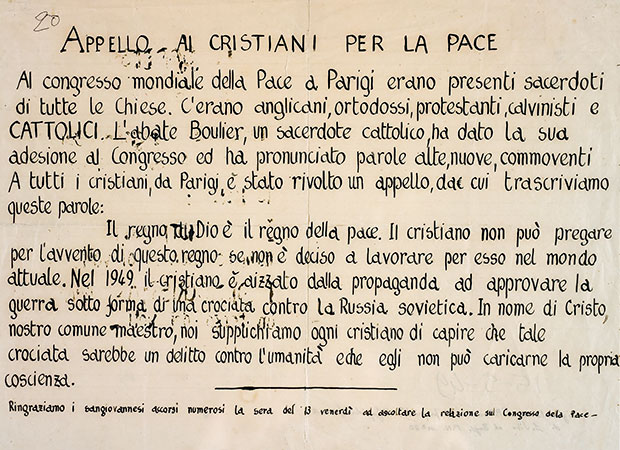

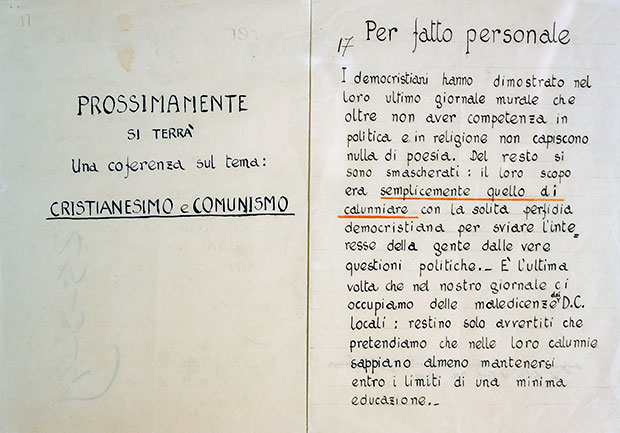

The last years of the 40ies were very hard for Casarsa: on one hand there were the threats of the annexation to the Yugoslavia; on the other hand the presence of fascism made the dissertation confused for those who lay claim for friulian independence. In 1947 Pier Paolo was politically active: at the beginning he joined the Movimento Popolare per l’Autonomia Friulana (Popular Movement for friulian Independence) from which he later moved away because of the unexpected pragmatic and pro-demo Christian leanings. Later Pasolini became a member of the Partito Comunista Italiano (Italian Communist Party). His sensitivity for people’s world was crucial for his communist choice, which strengthened and increased especially in the post-war years. The circumstances of his brother Guido’s death represented a difficulty to overcome even if Pier Paolo was sure that the episode of Porzùs was an exceptional event. The poet thought that the communism was the only way for a new culture, based on humanistic values and a moral interpretation of the existence. He got close to the PCI, he started contributing to the party’s weekly publication «Lotta e lavoro» (Struggle and work) and he enrolled in the branch of San Giovanni di Casarsa, where he became the clerk. In the little square of San Giovanni there was a Lodge dating back the XIV century in Venetian style. This building was closely related to Pier Paolo’s political involvement because here he posted his manifestoes: these were texts about the political debate, written both in italian and friulian. These provoked, in a contest of catholic and conservative preponderance, los of enemies. The manifestoes are partly preserved in the archive of Casarsa and they are shown in the room dedicated to the poet’s political involvement during the friulian period of his life.

[blockquote author=”Testo in friulano di uno dei manifesti politici, databili al 1948-49 e oggi conservati presso il Centro Studi di Casarsa” link=”” target=”_blank”]L’ANIMA NERA Se esia duta sta pulitica ch’a fan i predis cuntra di nualtris puares? A saressin lour cha varesin da vei il nustri stes penseir; a ni par che i nustri sintimins a sedin abastanza cristians! Sers democristians a si fan di maraveja se i Comunisc a van a Messa quant che i comunisc a podaressin fasì a mondi di pì maraveja par jodi chei democristians ch’a van a Messa cu l’anima nera coma il ciarbon.[/blockquote]

[idea]Traduzione:

L’ANIMA NERA Che cos’è tutta questa politica che fanno i preti contro noi poveri? Dovrebbero essere loro ad avere il nostro stesso pensiero; ci sembra che i nostri sentimenti siano abbastanza cristiani! Certi democristiani si meravigliano se i Comunisti vanno a Messa quando i comunisti potrebbero meravigliarsi di più a vedere quei democristiani che vanno a Messa con l’anima nera come il carbone.

[/idea]

The murals dated back to the spring and summer 1949. Pasolini expressed himself with the language of people and this represented a scandal in itself: the friulian communist intellectuals (who didn’t use the dialect) looked at this linguistic choice as a sort of indifference for the socialist realism and a consequent interest for the middle-class world. The idyllic friulian years brought to a dramatic end to which also these “politiche e furlane”(politic and friulian) debates took part.